Fleabag + Faith/Ep4

- Feb 16, 2021

- 3 min read

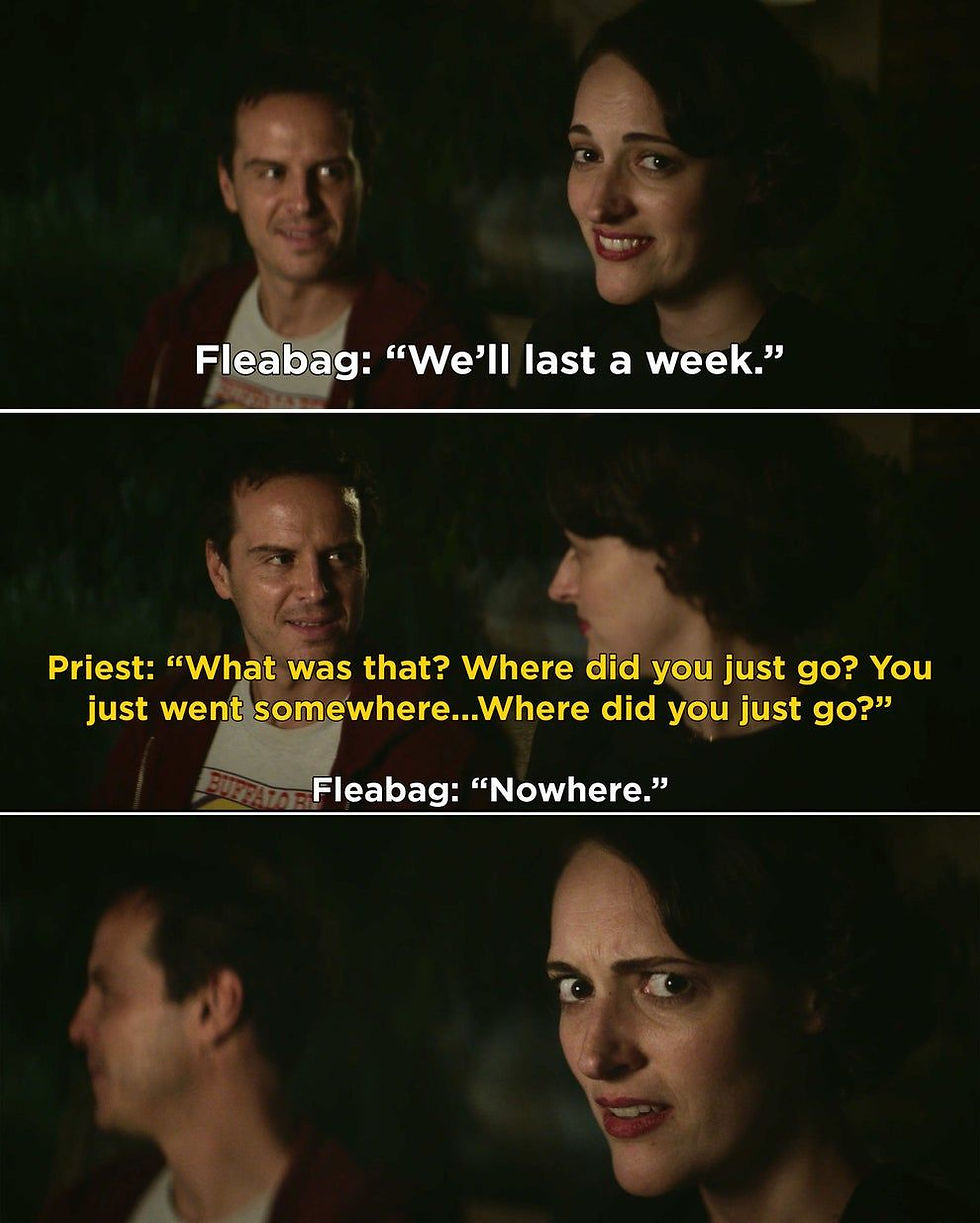

Another issue that is overtly discussed within Fleabag is that of sexuality, something that we tend to shy away from. Yet, there is nothing inherently wrong with the nature of sex itself - it is a beautiful act that brings forth life. The distortions that arise are how we view sex itself and its place in our relationships. Fleabag herself is no stranger to her own sexuality and is overtaken by desire most of the time (one of the reasons her father bought her a voucher for counselling). She uses sex to fill a deeper void - the connection that she wants. She comes away from her sexual liaisons not feeling much better than before and wondering why. In contemporary society, sex is sometimes viewed as a precondition for intimacy and full knowledge of another person. Yet, in that sense, we have lost a wider perspective of what intimacy truly means. While it encompasses the physical aspect, there is much more to explore and unpack. Fleabag’s promiscuity forms a smokescreen for genuine emotional connection as sex forms a temporary attempt at intimacy - it’s a one-night-stand that she doesn’t need to worry about catching feelings for. She confronts her struggle with these desires when she meets the Priest. She asks him about the subject of sex openly and he insists that sex is not possible as he has already made a promise to God. As the series wears on, Fleabag starts to Google about celibacy and its implications and it all seems like forbidden love at this point. Ignoring a person’s sexuality seems to be safer because we would rather pretend that we do not have such desires and are able to control them. Yet, we see distorted notions of sexuality prevalent in our own daily experience - some are far removed in stories of friends who have been sleeping around, some are closer to home in the form of friends who have become victims of harassment. The thing is therefore, is that it’s time to have an open and honest discussion about the role sexuality plays and how it affects our relationships.

At Fleabag’s insistence, the Priest eventually admits why he will not have sex with her. He admits that if he does, he will fall in love with her. This seems like a soppy narrative arc at first, but upon closer inspection I realised this echoed a central Catholic teaching on sex and marriage. The Priest views sex and love as one and the same - there cannot be one without the other. It points to the existence of sex within the structure of marriage - sex is an expression of spousal love, a total gift of self to other with the prospect of bringing forth new life in the process. I was stunned to realise the depth of what the Priest was saying - the bonds of sexual union are no different from the bonds of love between man and woman. The fact that the two eventually give in to temptation, is not necessarily an opportunity to judge them for what they have done but to realise that we are all fallen people, prone to temptation and that our human nature sometimes falls prey to our desires. Instead of being quick to judge the two, I came away with a more discerning outlook and was touched by the connection they shared. Guilt followed and the two broke up at a bus stop where the Priest admits that he has chosen God over Fleabag, but not before he utters the words - I love you too. Maybe sex and love do not necessarily mix, and maybe society has thrown it all into a swirling vortex of this search for meaning and intimacy but it reminds me that we are inherently made to love and for love, in whatever shape and form it looks like.

Comments